Ginger

Benefits

- Vitamins C, B6, iron, magnesium, potassium, manganese, niacin, zinc

- Antioxidant

- Anti-Inflammatory

- Improves brain function

- Treats nausea

- Promotes proper digestion

- Protects against stomach ulcers

- Eases menstrual pain

- Regulates blood sugar

Sources and Composition

Sources and Background

Ginger is the common name for the root of Zingiber officinale Roscoe, a plant that has historical precedence as both medicine and spice and is one of the more commonly used spices in the world.[4] Historical uses for ginger include headaches and migraines, blood pressure and flow, and colds.

The most commonly consumed part of ginger is the rhizome, or the vertical portion of the root.

Composition

The ginger root contains 14 main bioactives:

-

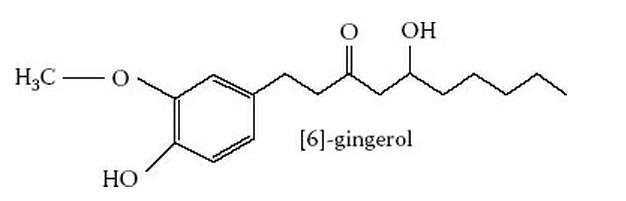

6-gingerol (long name of 1-(4′-hydroxy-3′- methoxyphenyl)-5-hydroxy-3-decanone), seen as the main bioactive and pictured below.[5] 6-Gingerol is not the only molecule in this class as 6-gingerol, 8-gingerol and 10-gingerol also exist in ginger.[6]

-

Methoxy-10-gingerol[6]

-

1,7-bis-(4′ hydroxyl-3′ methoxyphenyl)-5-methoxyhepthan-3-one[6]

-

10-gingerdione and 1-deoxy-10-gingerdione[6]

-

hexahydrocurcumin and tetrahydrocurcumin[6]

-

6-shogaol and 10-shogaol[6]

-

6-paradol[6]

-

Gingerenone A[6]

-

Galanal A and B[7]

Other compounds, found in many plants, are also found in Ginger Root:

-

Kaempferol, at a rather low dose of 0.068mg/g dry weight rhizome[8]

-

Two of the Green tea catechins, catechin and epicatechin up to 0.19 and 0.56mg/g leaf dry weight respectively[8]

-

Rutin, around 0.2mg/g in leaves and 0.4mg/g rhizome by dry weight[8]

-

Naringenin, usually around 0.04mg/g leaves and 0.02mg/g rhizome dry weight[8]

-

Curcumin, which contributes to the yellow-ish color of the rhizome[7]

The total phenolic content of ginger has at one time been calculated to be 157mg/100g fresh weight rhizome and 291mg/100g fresh weight leaves.[8] The total flavonoid content appears to be 5.54-11.4mg/g dry weight, which is above that of garlic, onions, papaya, black tea and semambu leaves all by at least two-fold.[8] The flavonoid content seems to shift from the leaves to the rhizome during aging, with more mature plants localizing the nutrients to the rhizome.[8]

Of the above, 6-gingerol appears to be the present in the highest amounts in ginger[9] despite variations in exact levels of these molecules based on preparation, source of ginger, and freshness.[10]

Gingerol

Gingerol is the primary pungent ingredient in Ginger, a ketone body structurally similar to raspberry ketones and capsaicin.

Pharmacology

Metabolism

6-Gingerol has been noted to be partially subject to glucuronidation, with the UGT1A1, 2B7 and 1A3 enzymes mediating conversion into a phenolic derivative while UGT1A9 mediated conversion into an alcohol derivative.[11]-gingerol|published=2006 Nov 15|authors=Pfeiffer E1, Heuschmid FF, Kranz S, Metzler M|journal=J Agric Food Chem]Neurology

Serotonergic Neurotransmission

When looking at the serotonin receptors, it appears that many compounds in ginger have affinity for the 5-HT2B receptor including 8-Shogaol (Ki value of 1.8µM), 10-Gingerol (4.2µM), 10-Dehydrogingerdion (7.6µM), 10-Gingerdione (12.5µM), and 8-Gingerol (25.4µM).[12] There appears to be weak affinity (greater than 10µM) for the 5-HT2C receptor from most ginger phenolics except for 8-Shogaol, which has a Ki of 3.8µM.[12] The basic ginger phenolics have failed to demonstrate affinity for the 5-HT6 receptor in vitro.[12]Appetite

2g of Ginger, taken with a meal, can slightly but significantly reduce the sensation of hunger and subsequent caloric intake (with no effect on satiety).[13]Cognition

Oral doses of 400-800mg Ginger extract (7.3% 6-gingerol, 1.34% 6-shogaol) to otherwise healthy women (aged 54+/-3.57) over a period of 2 months was associated with an increaes of N100 amplitude and P300 amplitude (event-related potentials) at the 800mg dose and both doses, respectively.[14] This study also noted, more practically, showed improvements (accuracy and speed) in word recognition tests and working memory (numeric and spatial) as well as improved choice reaction times.[14] In rats subject to right middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) Ginger at 100, 200, and 300mg/kg and noted that ginger at all doses was able to improve the rate of spatial memory improvement after occlusion by 7 days, improving up to 21 days.[15] This study also used Piracetam as an active control at 250mg/kg, and Piracetam was quicker at returning spatial memory after occlusion, and no tested drug influenced retention time. Both Piracetam and the two lower doses of ginger were effective in increasing hippocampal neuronal density after 21 days, but to a lesser extent than Aricept (another positive control drug).[15] In regards to brain infarct size after occlusion, Ginger at 200mg/kg was more effective than all positive controls at reducing the size of infarct after occlusion despite not being significantly better at preserving levels of endogenous anti-oxidant enzymes.[15]Interactions with Glucose Metabolism

Blood Glucose

Ginger, via its actions as a serotonin receptor antagonist, can increase insulin release from INS-1 cells, a research cell line for pancreatic beta-cells.[16] Serotonin normally suppresses insulin release in these cells, and antagonizing the 5-HT(3) receptor can alleviate this suppression and lead to a reduction in blood glucose; the reduction may be up to 35% in rats[16] and shows some effects in type I diabetic rats as well, despite less beta-cells.[17] 1g of ginger root, taken orally in healthy humans, seems to be ineffective in significantly reducing blood glucose (showing non-significant trends) but can alleviate some of the effects of high blood sugar, such as reduced gastric motility.[18]Obesity and Fat Mass

Thermic Effect of Food

At least one study has noted that Ginger, when taken at 2g alongside a (mostly carbohydrate) meal, is able to increase the caloric expenditure over the next 6 hours from that meal.[13] Consumption of 2g ginger was associated with an average 43+/-21kcal increase in metabolic rate among a sample of 10 men and relative to no ginger.[13] Overall metabolic rate independent of food was not affected.May enhance the thermic effect of food, and increase metabolic rate (slighty; 43+/-21 calories) in the context of a large meal

Interactions with Digestion and Nausea

Nausea

Ginger has been historically recommended to alleviate nausea and seasickness and appears to be more potent at suppressing sea sickness than Dimenhydrinate (Gravol).[19][20] It appears to exert these effects gastrically rather than neurally,[21] and can speed up gastric digestion, although the increase in motility is not the mechanism by which it alleviates nausea.[22][23] Due to interactions with the GI tract, many side-effects of taking nausea occur here; usually slight gastrointestinal complications after ingestion.[24]Motility

Ginger ingestion may have the ability to speed up gastric (stomach) transit of foods. It shows most benefit during states in which gastric motility would normally be suppressed, such as during sickness (nausea)[25], hyperglycemia[18] or disease state.[26][27] It can occur in healthy persons via stimulating antral contractions, but due to being less potent it bridges statistical significance, with some positive[28][23] and negative[22] results. The effects of ginger on gastric motility appear to be independent of a meal.[28]Stomach

A study on ginger and its effects on the Lower Esophageal Sphincter (LES) found that 1g of ginger was able to reduce LES pressure, which may exacerbate negative effects of heartburn in susceptible persons.[29]Flatulence

Ginger is known as having a 'carminative' effect, which is to break up and expel intestinal gas; it has traditionally been used to treat flatulence and gas.[29] This effect may be due to lowering of the lower esophageal sphincter above the stomach, which may cause gas produced in the stomach to leave orally rather than rectally.[29]Usage in Pregnancy

Morning Sickness

Its effects on morning sickness, at a dose of 1g, either parallels that of 75mg Vitamin B6[30][31] or is slightly more effective.[32] At least one study that upped the dosage of Ginger to 1,950mg found that it was more effective than 75mg Vitamin B6, however.[33] Ginger is approximately as effective as metoclopramide (pharmaceutical), if not slightly less effective.[34] When compared to dimenhydrinate, ginger appears to have a delayed time to effectiveness (in which dimenhydrinate is more effective for the first two days, then the differences are insignificant) whereas it does not have the drowsiness associated with Dimenhydrinate.[35]The research on nausea in general can quite reliably be extrapolated to alleviating nausea associated with pregnancy, and ginger appears to be effective. As to whether it is safe or not for pregnancy, short term (4 week or less) usage appears to be safe from obvious side-effects with longer usage unknown

Dysmenorrhea

Ginger has twice been shown to reduce the pain associated with periods in women at a dose of 1g daily, both times when taken as four divided dosages of 250mg.[36][37] It is as effective as ibuprofen and mefenamic acid in this regard.[37] A two-month placebo-controlled trial among high school students not on birth control with primary dysmennorrhea saw a reduction of pain as measured by a visual analog scale of 22% the first month and 61% the second month with ginger use.[38] The dose given was 250mg ginger powder three times a day for four days, starting the day before menstural bleeding commenced.[38]Interactions with Hormones

estosterone

An aqueous extract of Ginger (600mg/kg bodyweight) has been found to increase serum testosterone, weight of testes, and testicle cholesterol content in otherwise healthy rats.[39] Another study using dosages of 500mg/kg and 1g/kg bodyweight found dose-dependent increases in seminal quality as well as dose-dependent increases in testosterone, from around 0.3nmol/L at baseline nearing 0.6nmol/L after 14 days with minimal differences existing between 14 and 28.[40] Testosterone increasing effects have been reported in rats as low as 100mg/kg bodyweight (powdered extract), with control at 1.60±0.091ng/mL to 3.71±0.387ng/mL at 100mg/kg daily.[41] There were increases in testosterone at 50mg/kg daily in this study, but it did not reach statistical significance.[41] Although testicle size increased after 14 and 28 days supplementation, this may be due to hypertrophy of the epididymus. Seminal sacs and the prostate were unchanged.[42] After gavage feeding of 2000mg/kg per day for 35 days (very high dose) there appears to be decreases in testicle size and weight.[43] This was hypothesized by the authors to be due to a negative feedback reaction from androgenic activity.[43] Gingerol has been implicated in preventing downstream signalling of testosterone involving prostate hypertrophy, as seen in LNCaP cells where gingerol incubation reduces prostate-specific antigen secretion induced from testosterone (up to 21%).[44] Gingerol also induced apoptosis in these cells, and was able to reduce the increase in prostate size associated with testosterone in experimental animals.[44] In studies where damage occurs to reproductive organs, ginger shows efficacy in preventing oxidative damage induced by aluminum chloride[45] and alleviate the reduction in sexuality associated with diabetes.[46] Twice ginger has been implicated in reducing cisplatin induced testicular damage.[47][48] The mechanisms of ginger on testosterone are not really known. Past letters (in response to trials) suggest it may be via thromboxane inhbition,[49] an effect shared between ginger and the reference drug cimetidine. However, Cimetidine appears to be an anti-androgen[50] (opposite that of ginger) and this theorized mechanism of action may not be legitimate.Ginger appears to be effective in increasing testosterone concentrations in rodentsIn a study of infertile men, the improvements in fertiliy and seminal parameters observed with three months of therapy was associated with a 17.7% increase in testosterone concentrations; dosage of ginger used was not specified.[51]

Preliminary evidence to support the usage of ginger to boost testosterone concentrations, although this has only been demonstrated in infertile men at this point in time

Estrogen

One study assessing a variety of medical plants for estrogenic properties noted that Ginger was able to activate the estrogen receptor in a yeast assay with an EC50 of 77.26ug/mL when the 95% ethanolic extract was tested; a similar potency to Glycyrrhiza Uralensis.[52]Interactions with Peripheral Organ Systems

Testicles

Supplementation of ginger to infertile men (3 months of therapy, dosage not specified) appears to be able to increase sperm count (16.2%), motility (47.3%), viability (40.7%), normal morphology (18.4%), and ejaculate volume (36.1%) paired with reductions in lipid peroxidation as assessed by MDA (53.7%) and increases in glutathione 26.7%).[51]Nutrient-Nutrient Interactions

5-HTP

5-HTP is the amino acid precursor to serotonin, a neurotransmitter commonly associated with happiness and contentment. Ginger has actions as a serotonin receptor antagonist, of which many are located in the intestines. These effects seem to be mediated through gingerols and their metabolites.[53] Oral treatment of ginger (as juice) has been shown in rats to negate the hyperglycemia induced by serotonin;[17] this hyperglycemia normally occurs as serotonin suppresses insulin secretion, and inhibiting this reaction causes a relative reduction in blood glucose. As the serum levels of gingerols in the brain appears to be ten-fold lower than the level in the intestines and stomach after ingestion,[54] it seems that, practically, this antagonism may only be relevant to serotonin's gastrointestinal and systemic interactions.May counteract any intestinal action of serotonin and its precursor, and thus combination would not be advised. May not adversely interact with neural actions of serotonin due to too low a dose used.

Magnolia Officinalis

Magnolia Officinalis, or Magnolia Bark, is a herbal product which is typically reduced to its two active ingredients 'Magnolol' and 'Honokiol'; its effects on anti-depression (at 20mg/kg bodyweight combined) are synergistically enhanced when coingested with ginger at 14mg/kg bodyweight in rats despite ginger having no anti-depressive effects in isolation.[55]Safety and Toxicity

General

In meta-analysis' and reviews conducted on the topic, side-effects reported in clinical trials appear to be related to gastrointesinal discomfort and never more severe.[56][57][3] These occur infrequently at the recommended 1-2g dosage range for Nausea prevention. Studies in rats suggest that, when fed orally (gavage) there are no significant adverse changes in blood chemistry or organ weight up to dosages of 2000mg/kg bodyweight for 35 days, with exception to a decrease in testicle size possible due to a negative feedback response from androgenic activity.[43] This dose is 320mg/kg bodyweight daily when converted to humans based on Body Surface Area. Lower dosages (500mg/kg) have been tested for up to 13 weeks in rats of both genders with no side-effects noted.[58]In pregnancy

A meta-analysis of 6 randomized trials noted that there were no reports of adverse effects associated with Ginger in the 6 studies selected as it pertains to pregnancy.[59] Another review[3] specifically investigated four trials[60][61][62][30] and found no adverse effects at a dosage of 1g Ginger Extract.Interactions

Due to an anticoagulant effect of ginger, it should not be paired with pharmaceutical (prescription) drugs with the same effect such as Warfarin, and possibly NSAIDs such as Aspirin; doubly important when used during pregnancy.[63]References

- ^ Yip YB, Tam AC. An experimental study on the effectiveness of massage with aromatic ginger and orange essential oil for moderate-to-severe knee pain among the elderly in Hong Kong. Complement Ther Med. (2008)

- ^ Food Bolus Intestinal Obstruction in a Chinese Population.

- ^ a b c Bryer E. A literature review of the effectiveness of ginger in alleviating mild-to-moderate nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. J Midwifery Womens Health. (2005)

- ^ Surh Y. Molecular mechanisms of chemopreventive effects of selected dietary and medicinal phenolic substances. Mutat Res. (1999)

- ^ The Amazing and Mighty Ginger.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Koh EM, et al. Modulation of macrophage functions by compounds isolated from Zingiber officinale. Planta Med. (2009)

- ^ a b Miyoshi N, et al. Dietary ginger constituents, galanals A and B, are potent apoptosis inducers in Human T lymphoma Jurkat cells. Cancer Lett. (2003)

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ghasemzadeh A, Jaafar HZ, Rahmat A. Identification and concentration of some flavonoid components in Malaysian young ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe) varieties by a high performance liquid chromatography method. Molecules. (2010)

- ^ Bailey-Shaw YA, et al. Changes in the contents of oleoresin and pungent bioactive principles of Jamaican ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe.) during maturation. J Agric Food Chem. (2008)

- ^ Schwertner HA, Rios DC, Pascoe JE. Variation in concentration and labeling of ginger root dietary supplements. Obstet Gynecol. (2006)

- ^ Microsomal hydroxylation and glucuronidation of [6.

- ^ a b c Takeda H, et al. Rikkunshito, an herbal medicine, suppresses cisplatin-induced anorexia in rats via 5-HT2 receptor antagonism. Gastroenterology. (2008)

- ^ a b c Mansour MS, et al. Ginger consumption enhances the thermic effect of food and promotes feelings of satiety without affecting metabolic and hormonal parameters in overweight men: A pilot study. Metabolism. (2012)

- ^ a b Saenghong N, et al. Zingiber officinale Improves Cognitive Function of the Middle-Aged Healthy Women. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. (2012)

- ^ a b c Wattanathorn J, et al. Zingiber officinale Mitigates Brain Damage and Improves Memory Impairment in Focal Cerebral Ischemic Rat. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. (2011)

- ^ a b Heimes K, Feistel B, Verspohl EJ. Impact of the 5-HT3 receptor channel system for insulin secretion and interaction of ginger extracts. Eur J Pharmacol. (2009)

- ^ a b Akhani SP, Vishwakarma SL, Goyal RK. Anti-diabetic activity of Zingiber officinale in streptozotocin-induced type I diabetic rats. J Pharm Pharmacol. (2004)

- ^ a b Gonlachanvit S, et al. Ginger reduces hyperglycemia-evoked gastric dysrhythmias in healthy humans: possible role of endogenous prostaglandins. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. (2003)

- ^ Mowrey DB, Clayson DE. Motion sickness, ginger, and psychophysics. Lancet. (1982)

- ^ Schmid R, et al. Comparison of Seven Commonly Used Agents for Prophylaxis of Seasickness. J Travel Med. (1994)

- ^ Holtmann S, et al. The anti-motion sickness mechanism of ginger. A comparative study with placebo and dimenhydrinate. Acta Otolaryngol. (1989)

- ^ a b Phillips S, Hutchinson S, Ruggier R. Zingiber officinale does not affect gastric emptying rate. A randomised, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. Anaesthesia. (1993)

- ^ a b Wu KL, et al. Effects of ginger on gastric emptying and motility in healthy humans. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2008)

- ^ Altman RD, Marcussen KC. Effects of a ginger extract on knee pain in patients with osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. (2001)

- ^ Stewart JJ, et al. Effects of ginger on motion sickness susceptibility and gastric function. Pharmacology. (1991)

- ^ Shariatpanahi ZV, et al. Ginger extract reduces delayed gastric emptying and nosocomial pneumonia in adult respiratory distress syndrome patients hospitalized in an intensive care unit. J Crit Care. (2010)

- ^ Hu ML, et al. Effect of ginger on gastric motility and symptoms of functional dyspepsia. World J Gastroenterol. (2011)

- ^ a b Micklefield GH, et al. Effects of ginger on gastroduodenal motility. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. (1999)

- ^ a b c Lohsiriwat S, et al. Effect of ginger on lower esophageal sphincter pressure. J Med Assoc Thai. (2010)

- ^ a b Smith C, et al. A randomized controlled trial of ginger to treat nausea and vomiting in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. (2004)

- ^ Sripramote M, Lekhyananda N. A randomized comparison of ginger and vitamin B6 in the treatment of nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. J Med Assoc Thai. (2003)

- ^ Ensiyeh J, Sakineh MA. Comparing ginger and vitamin B6 for the treatment of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy: a randomised controlled trial. Midwifery. (2009)

- ^ Chittumma P, Kaewkiattikun K, Wiriyasiriwach B. Comparison of the effectiveness of ginger and vitamin B6 for treatment of nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy: a randomized double-blind controlled trial. J Med Assoc Thai. (2007)

- ^ Mohammadbeigi R, et al. Comparing the effects of ginger and metoclopramide on the treatment of pregnancy nausea. Pak J Biol Sci. (2011)

- ^ Pongrojpaw D, Somprasit C, Chanthasenanont A. A randomized comparison of ginger and dimenhydrinate in the treatment of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy. J Med Assoc Thai. (2007)

- ^ Ozgoli G, Goli M, Simbar M. Effects of ginger capsules on pregnancy, nausea, and vomiting. J Altern Complement Med. (2009)

- ^ a b Ozgoli G, Goli M, Moattar F. Comparison of effects of ginger, mefenamic acid, and ibuprofen on pain in women with primary dysmenorrhea. J Altern Complement Med. (2009)

- ^ a b Kashefi F1, et al. Comparison of the effect of ginger and zinc sulfate on primary dysmenorrhea: a placebo-controlled randomized trial. Pain Manag Nurs. (2014)

- ^ Kamtchouing P, et al. Evaluation of androgenic activity of Zingiber officinale and Pentadiplandra brazzeana in male rats. Asian J Androl. (2002)

- ^ Effects of Zingiber Officinale on Reproductive Functions in the Male Rat.

- ^ a b The effects of ginger on spermatogenesis and sperm parameters of rat.

- ^ Effects of Zingiber Officinale on Reproductive Functions in the Male Rat.

- ^ a b c A 35-day gavage safety assessment of ginger in rats.

- ^ a b Shukla Y, et al. In vitro and in vivo modulation of testosterone mediated alterations in apoptosis related proteins by (6)-gingerol. Mol Nutr Food Res. (2007)

- ^ Moselhy WA, et al. Role of ginger against the reproductive toxicity of aluminium chloride in albino male rats. Reprod Domest Anim. (2012)

- ^ Shalaby MA, Hamowieh AR. Safety and efficacy of Zingiber officinale roots on fertility of male diabetic rats. Food Chem Toxicol. (2010)

- ^ Amin A, Hamza AA. Effects of Roselle and Ginger on cisplatin-induced reproductive toxicity in rats. Asian J Androl. (2006)

- ^ Amin A, et al. Herbal extracts counteract cisplatin-mediated cell death in rat testis. Asian J Androl. (2008)

- ^ Backon J. Ginger in preventing nausea and vomiting of pregnancy; a caveat due to its thromboxane synthetase activity and effect on testosterone binding. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. (1991)

- ^ Winters SJ, Banks JL, Loriaux DL. Cimetidine is an antiandrogen in the rat. Gastroenterology. (1979)

- ^ a b The effect of Ginger on semen parameters and serum FSH, LH & testosterone of infertile men.

- ^ Kim IG, et al. Screening of estrogenic and antiestrogenic activities from medicinal plants. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. (2008)

- ^ Abdel-Aziz H, et al. 5-HT3 receptor blocking activity of arylalkanes isolated from the rhizome of Zingiber officinale. Planta Med. (2005)

- ^ Jiang SZ, Wang NS, Mi SQ. Plasma pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution of {6}-gingerol in rats. Biopharm Drug Dispos. (2008)

- ^ Qiang LQ, et al. Combined administration of the mixture of honokiol and magnolol and ginger oil evokes antidepressant-like synergism in rats. Arch Pharm Res. (2009)

- ^ Chaiyakunapruk N, et al. The efficacy of ginger for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting: a meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. (2006)

- ^ Thompson HJ, Potter PJ. Review: ginger prevents 24 hour postoperative nausea and vomiting. Evid Based Nurs. (2006)

- ^ Jeena K, Liju VB, Kuttan R. A preliminary 13-week oral toxicity study of ginger oil in male and female Wistar rats. Int J Toxicol. (2011)

- ^ Borrelli F, et al. Effectiveness and safety of ginger in the treatment of pregnancy-induced nausea and vomiting. Obstet Gynecol. (2005)

- ^ Fischer-Rasmussen W, et al. Ginger treatment of hyperemesis gravidarum. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. (1991)

- ^ Vutyavanich T, Kraisarin T, Ruangsri R. Ginger for nausea and vomiting in pregnancy: randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. (2001)

- ^ Keating A, Chez RA. Ginger syrup as an antiemetic in early pregnancy. Altern Ther Health Med. (2002)

- ^ Tiran D. Ginger to reduce nausea and vomiting during pregnancy: evidence of effectiveness is not the same as proof of safety. Complement Ther Clin Pract. (2012)

- Grøntved A, Hentzer E. Vertigo-reducing effect of ginger root. A controlled clinical study. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. (1986)

- Zick SM, et al. Phase II study of the effects of ginger root extract on eicosanoids in colon mucosa in people at normal risk for colorectal cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). (2011)

- Cady RK, et al. A double-blind placebo-controlled pilot study of sublingual feverfew and ginger (LipiGesic™ M) in the treatment of migraine. Headache. (2011)

- Willetts KE, Ekangaki A, Eden JA. Effect of a ginger extract on pregnancy-induced nausea: a randomised controlled trial. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. (2003)

- Bliddal H, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled, cross-over study of ginger extracts and ibuprofen in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. (2000)

- Black CD, et al. Ginger (Zingiber officinale) reduces muscle pain caused by eccentric exercise. J Pain. (2010)

- Black CD, Oconnor PJ. Acute effects of dietary ginger on quadriceps muscle pain during moderate-intensity cycling exercise. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. (2008)

- Zahmatkash M, Vafaeenasab MR. Comparing analgesic effects of a topical herbal mixed medicine with salicylate in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Pak J Biol Sci. (2011)

- Ernst E, Pittler MH. Efficacy of ginger for nausea and vomiting: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Br J Anaesth. (2000)

- Pillai AK, et al. Anti-emetic effect of ginger powder versus placebo as an add-on therapy in children and young adults receiving high emetogenic chemotherapy. Pediatr Blood Cancer. (2011)

- Cady RK, et al. Gelstat Migraine (sublingually administered feverfew and ginger compound) for acute treatment of migraine when administered during the mild pain phase. Med Sci Monit. (2005)

- Alizadeh-Navaei R, et al. Investigation of the effect of ginger on the lipid levels. A double blind controlled clinical trial. Saudi Med J. (2008)

- Apariman S, Ratchanon S, Wiriyasirivej B. Effectiveness of ginger for prevention of nausea and vomiting after gynecological laparoscopy. J Med Assoc Thai. (2006)

- Nanthakomon T, Pongrojpaw D. The efficacy of ginger in prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting after major gynecologic surgery. J Med Assoc Thai. (2006)

- Khayat S, et al. Effect of treatment with ginger on the severity of premenstrual syndrome symptoms. ISRN Obstet Gynecol. (2014)